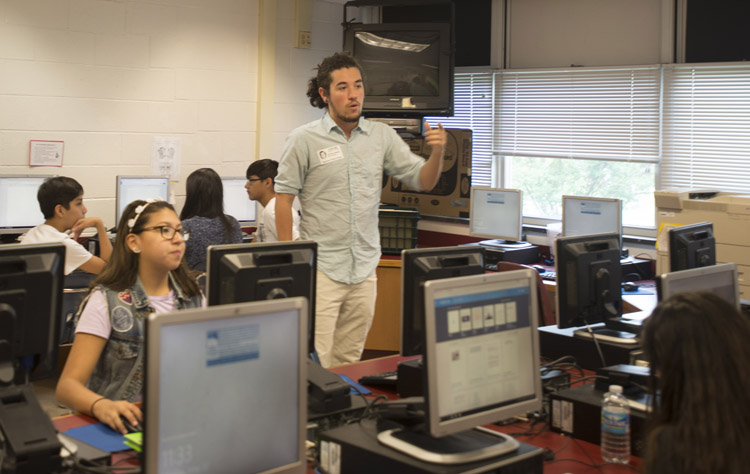

Recent graduate in game and design, Shipley Owens, uses vintage video games to help students who weren't performing well on standardized tests at Stonewall Middle School in Manassas. Photo by Jamie Rogers.

A small pack of giggling, talkative teens streams into a classroom and takes seats in front of computers just as the soft chime of the Stonewall Middle School bell sounds.

It’s their last class session with Shipley Owens, a computer game and design senior at George Mason University. With his big hair and thin frame, he could pass as one of their classmates.

Since the fall, Owens and Stonewall literacy coach Elizabeth Jones have collaborated on teaching the students in Jones’ Reading Strategies class to improve their literary skills.

The class is for eighth-graders who failed their reading Standards of Learning (SOL), a standardized test administered to Virginia’s secondary education students.

Owens got involved with the course after Jones reached out to Vera Lichtenberg, the director of the Mason Game and Technology Academy, to learn more about using video games to engage students.

Research shows video games can be a tool in the modern digital era for developing literacy cognition, maintaining engagement and creating social change, Jones said.

“Initially, I thought video games were a problem,” Jones said. “However, after a conversation with my students, I realized my perspective about video games and literacy was the problem.”

Jones asked her students to explain what they knew about first-person and third-person shooter games.

“Suddenly, the students who initially were reluctant to participate were enthusiastically sharing experiences, using technical and academic vocabulary, and making connections,” she said. “That day I learned video games were not a waste of time.”

Together Owens and Jones use vintage video games to help the students understand literary concepts like character conflicts, narratives, and first- and third-person perspectives.

The games are low-tech and simple enough that students can identify a character’s conflict and the game’s narrative, Owens said.

The curriculum for the class, designed by Owens and Jones, incorporates elements of a narrative design course for higher schoolers Owens taught with Mason computer game and design professor Seth Hudson last summer through the Mason Game and Technology Academy.

“The goal at Stonewall was the writing of game narrative,” Owens said. “We were teaching students how to analyze literature.”

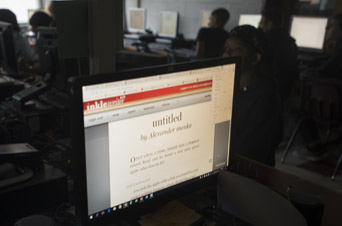

A computer monitor in the classroom shows Inklewriter, the program students use to tell stories. Photo by Jamie Rogers.

On his last day, Owens and the class reviewed a writing project they’d done in the fall as a way to assess how far their skills had progressed.

The students crafted a video game narrative through a program called Inklewriter, which allows users to write a story and then input choices for what a character can do next. The story can then be used as a video game script.

“Because the subject matter was video games, it was more intriguing and appealing to the students,” Owens said.

The class has developed the students’ self-confidence and critical thinking skills, Jones said.

“Their attitudes about reading have changed and improved in many ways,” she said. “I believe their reading SOL scores will reflect their growth in reading.”

Owens, who participated in Commencement in May but is wrapping up his degree studies this summer, said he would like to continue his work at Stonewall in the fall. The Columbia, Md., native just accepted a position at a Manassas-based game design studio.